Sunset on Mont Blanc

From The Playground of Europe by Leslie Stephen 1871

And now, whilst occupied in drinking in that strange sensation, and allowing our minds to recover their equilibrium from the first staggering shock of astonishment, began the strange spectacle of which we were the sole witnesses. One long delicate cloud, suspended in mid-air just below the sun, was gradually adorning itself with prismatic colouring. Round the limitless horizon ran a faint fog-bank, unfortunately not quite thick enough to produce that depth of colouring which sometimes makes an Alpine sunset inexpressibly gorgeous. The weather — it was the only complaint we had to make — erred on the side of fineness. But the colouring was brilliant enough to prevent any thoughts of serious disappointment. The long series of western ranges melted into a uniform hue as the sun declined in their rear. Amidst their folds the Lake of Geneva became suddenly lighted up in a faint yellow gleam. To the east a blue gauze seemed to cover valley by valley as they sank into night and the intervening ridges rose with increasing distinctness, or rather it seemed that some fluid of exquisite delicacy of colour and substance was flooding all the lower country beneath the great mountains. Peak by peak the high snow-fields caught the rosy glow and shone like signal-fires across the dim breadths of delicate twilight. Like Xerxes, we looked over the countless host sinking into rest, but with the rather different reflection, that a hundred years hence they would probably be doing much the same thing, whilst we should long have ceased to take any interest in the performance. And suddenly began a more startling phenomenon. A vast cone, with its apex pointing away from us, seemed to be suddenly cut out from the world beneath; night was within its borders and the twilight still all round; the blue mists were quenched where it fell, and for the instant we could scarcely tell what was the origin of this strange appearance. Some unexpected change seemed to have taken place in the programme; as though a great fold in the curtain had suddenly given way, and dropped on to part of the scenery. Of course a moment's reflection explained the meaning of this uncanny intruder; it was the giant shadow of Mont Blanc, testifying to his supremacy over all meaner eminences. It is difficult to say how sharply marked was the outline, and how startling was the contrast between this pyramid of darkness and the faintly-lighted spaces beyond its influence ; a huge inky blot seemed to have suddenly fallen upon the landscape. As we gazed we could see it move. It swallowed up ridge by ridge, and its sharp point crept steadily from one landmark to another down the broad Valley of Aosta. We were standing, in fact, on the point of the gnomon of a gigantic sundial, the face of which was formed by thousands of square miles of mountain and valley. So clear was the outline that, if figures had been scrawled upon glaciers and ridges, we could have told the time to a second ; indeed, we were half-inclined to look for our own shadows at a distance so great that whole villages would be represented by a scarcely distinguishable speck of colouring. The huge shadow, looking ever more strange and magical, struck the distant Becca di Nona, and then climbed into the dark region where the broader shadow of the world was rising into the eastern sky. By some singular effect of perspective, rays of darkness seemed to be converging from above our heads to a point immediately above the apex of the shadowy cone. For a time it seemed that there was a kind of anti-sun in the east, pouring out not light, but deep shadow as it rose. The apex soon reached the horizon, and then to our surprise began climbing the distant sky. Would it never stop, and was Mont Blanc capable of overshadowing not only the earth but the sky? For a minute or two I fancied, in a bewildered way, that this unearthly object would fairly rise from the ground and climb upwards to the zenith. But rapidly the lights went out upon the great army of mountains ; the snow all round took the livid hue which immediately succeeds an Alpine sunset, and almost at a blow the shadow of Mont Blanc was swallowed up in the general shade of night.

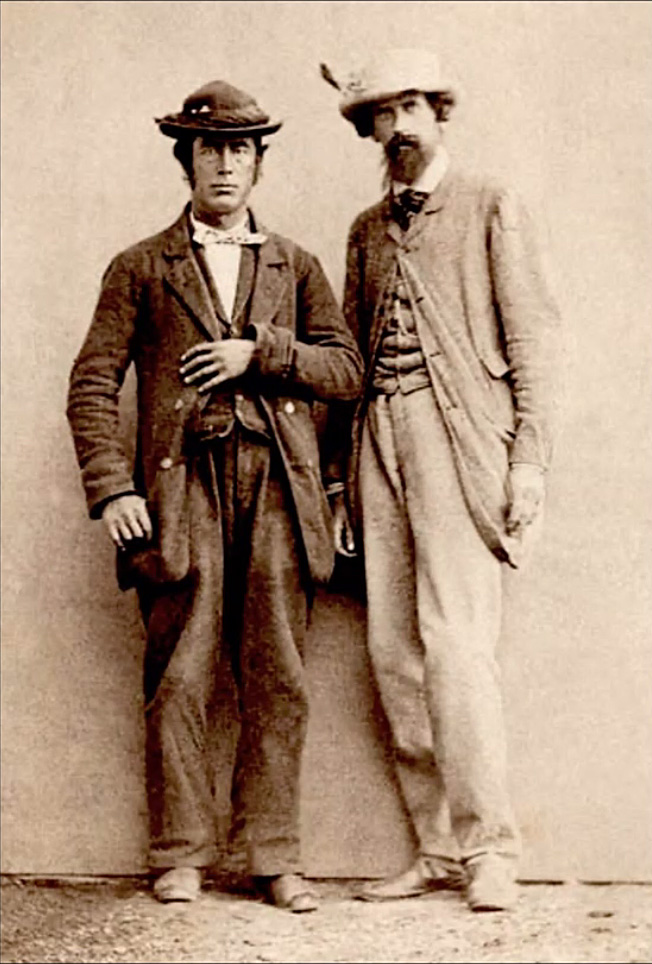

Mont Blanc sunset, by Gabriel Loppé : one of the foreground figures is Leslie Stephen

The display had ceased suddenly at its culminating point, and it was highly expedient for the spectators to retire. We had no time to lose if we would get off the summit before the grip of the frost should harden the snows into an ice-crust; and in a minute we were running and sliding downwards at our best pace towards the familiar Corridor. Yet as we went the sombre magnificence of the scenery seemed for a time to increase. We were between the day and the night. The western heavens were of the most brilliant blue with spaces of transparent green, whilst a few scattered cloudlets glowed as if with internal fire. To the east the night rushed up furiously, and it was difficult to imagine that the dark purple sky was really cloudless and not blackened by the rising of some portentous storm. That it was, in fact, cloudless, appeared from the unbroken disc of the full moon, which, if I may venture to say so, had a kind of silly expression, as though it were a bad imitation of the sun, totally unable to keep the darkness in order.

With how sad steps, O moon, thou climb'st the sky,

How silently and with how wan a face!

as Sidney exclaims. And truly, set in that strange gloom, the moon looked wan and miserable enough ; the lingering sunlight showed by contrast that she was but a feeble source of illumination; and, but for her half-comic look of helplessness, we might have sympathised with the astronomers who tell us that she is nothing but a vast perambulating tombstone, proclaiming to all mankind in the words of the familar epitaph, “As I am now, you soon shall be!” To speak after the fashion of early mythologies, one might fancy that some supernatural cuttlefish was shedding his ink through the heavens to distract her, and that the poor moon had but a bad chance of escaping his clutches. Hurrying downwards with occasional glances at the sky, we had soon reached the Grand Plateau, whence our further retreat was secure, and from that wildest of mountain fastnesses we saw the last striking spectacle of the evening. In some sense it was perhaps the most impressive of all. As all Alpine travellers know, the Grand Plateau is a level space of evil omen, embraced by a vast semicircle of icy slopes. The avalanches which occasionally descend across it, and which have caused more than one catastrophe, give it a bad reputation; and at night the icy jaws of the great mountain seem to be enclosing you in a fatal embrace. At this moment there was something half grotesque in its sternness. Light and shade were contrasted in a manner so bold as to be almost bizarre. One half of the cirque was of a pallid white against the night, which was rushing up still blacker and thicker, except that a few daring stars shone out like fiery sparks against a pitchy canopy; the other half, reflecting the black night, was relieved against the last gleams of daylight; in front a vivid band of blood-red light burnt along the horizon, beneath which seemed to lie an abyss of mysterious darkness. It was the last struggle between night and day, and the night seemed to assume a more ghastly ferocity as the day sank, pale and cold, before its antagonist. The Grand Plateau, indeed, is a fit scene for such contrasts; for there in mid-day you may feel the reflection of the blinding snows like the blast of a furnace, where a few hours before you were realising the keenest pangs of frost-bite. The cold and the night were now the conquerors, and the angry sunset glow seemed to grudge the victory. The light rapidly faded, and the darkness, no longer seen in the strange contrast, subsided to its ordinary tones. The magic was gone; and it was in a commonplace though lovely summer night that we reached our resting-place at the Grands Mulets. We felt that we had learnt some new secrets as to the beauty of mountain scenery, but the secrets were of that kind which not even the initiated can reveal. A great poet might interpret the sentiment of the mountains into song; but no poet could pack into any definite proposition or series of propositions the strange thoughts that rise in different spectators of such a scene. All that I at last can say is that some indefinable mixture of exhilaration and melancholy pervades one's mind; one feels like a kind of cheerful Tithonus “at the quiet limit of the world,” looking down from a magic elevation upon the “dim fields about the homes”

Of happy men that have the power to die.

One is still of the earth, earthy; for freezing toes and snow-parched noses are lively reminders that one has not become an immortal. Even on the top of Mont Blanc one may be a very long way from heaven. And yet the mere physical elevation of a league above the sea level seems to raise one by moments into a sphere above the petty interests of everyday life. Why that should be so, and by what strange threads of association the reds and blues of a gorgeous sunset, the fantastic shapes of clouds and shadows at that dizzy height, and the dramatic changes that sweep over the boundless region beneath your feet, should stir you like mysterious music, or, indeed, why music itself should have such power, I leave to philosophers to explain. This only I know, that even the memory of that summer evening on the top of Mont Blanc has power to plunge me into strange reveries not to be analysed by any capacity, and still less capable of expression by the help of a few black remarks on white paper.

Leslie Stephen (right) and his guide, presumably Melchior Anderegg

Leslie Stephen's daughter Virginia Woolf wrote a short account of him, including her impressions of his early life in the Alps. download pdf