A ghost story for Christmas

Golf balls of the material world

3000 words 12 minutes read

"Thirty-seven," said Hector Sanderson. He says it in a neutral tone – or tries to, at least. Because, Rules of Golf: The ball that is farther from the hole shall be played first. Which means that Sanderson can't play his second shot until, somehow, I've played my own ball another 30 yards up the fairway.

My tee shot connected first time – and straight up the middle. Pretty good, given the poor playing conditions, the pre-dawn light as dense cloud scuds across, not to mention the wind still brisk after the overnight storm. But now my concentration has slipped. This time – I prepare my swing. Eye on the ball, Fraser. The lie's good, and now –

Along the fairway's edge, something's moving. The dark shadow of a person, hunched against the rain. But my swing is already started – down, through: in my imagination I hear the satisfying clunk of wood on golfball.

I look down. The ball still lies there, in front of me, a little white glow in the half-light. "Thirty-eight," Hector says.

It was Colonel Mackenzie, of course, out on the fairway at three in the morning. The old army officer – yes, the army has women in it now, just like the Club itself. If I'd been still around for that meeting I'd have voted against, of course I should. But you know what, I'd have been wrong. Watching the Colonel and her colleagues all these years, their playing style, respect for the Rules of Golf. No, they hadn't lowered the tone of the Club. Rather the opposite, to some extent.

Not that the Colonel's a member, not any more. Small matter of the subscription.

The Colonel, these days, is what we call a Supernumerary. An unpaid volunteer, basically. Though I know, because I've seen her, that once all the Members are away in the bar she'll play a hole or two, on her own and strictly against the Rules. Particular fondness for this hole, as it happens: the Eleventh, known to its friends as the Horse's Arse.

But now she's walking down the fairway's edge. She is looking at the lost balls, the ones she fetched out of the rough yesterday evening, the ones she left along the edge of the playing area.

She's noticing that two of them have moved. And now, looking out across the fairway –

Where one of those balls is lying, right out in the open. Both of them in fact, Sanderson's one just 30 yards further up the fairway. And now the Colonel is walking out towards us. Stops right here, looks down at my ball where it lies. Quite a good lie, as I mentioned before, no excuse really for not managing to hit the thing.

Not managing, thirty-seven times.

She looks down at the ball, probably liking the lie as much as I do. Rain running down her sou'wester hat, grey hair damp against her shoulders. Gabardine jacket, shabby now but still holding out the water, and the sensible tweed skirt. I've always rather admired the sensible tweed skirt.

I step back smartly as she moves round to my side of the ball, stands looking down at it as if to take the next shot, just supposing she had a club in her hands. Then she turns round, faces directly towards me.

Behind her, the clouds are breaking, the sunrise in streaks of custard yellow. Beyond the trees, over on the seventh fairway, the wild dogs are howling.

"Fraser?" she said. "Fraser, is that you?" And I realise she can see me, is looking straight at me, dim shadow as I am.

Dim, dead shadow. Dead these ninety-five years.

•••

"Colonel Mackenzie," I say. "Well, well. Delighted to make your acquaintance." I'm not sure if she'll hear my voice; first time, in fact, that I've tried to use it on somebody who's still alive. But she does, leaning forward, intelligent look in her wrinkled old eyes. "Surprised you recognised me, though. You, of course, very like your great-grandfather. Same little jerk on the backswing."

"Well Fraser, you did design this golf course, back in the day. Your picture's still up at the back of the bar. They won't let me in the car park, but I am allowed in the bar, just so long as it's a quiet time."

The sun's up now, throwing long bars of shadow across the fairway. The duck pond, filled by the overnight rain, is spreading brown water past the red-topped penalty posts and out across the fairway. "With your permission, Sanderson: Colonel, why don't you play along with us? Make it a three-ball."

"Well, but my clubs –"

"I happen to know you keep a five-iron hidden under the gorse bushes over there. Chip one of those balls over, and start playing. Eleventh hole, par four. Do they still call it the Horse's Arse?"

Colonel Mackenzie's a powerful left-hander: Sanderson looks slightly miffed as her five-iron shot bounces right over the eponymous Horse's Arse bunker and rolls to a stop just short of the green. I address my own ball again. Backswing and – strike.

Once again, my ball remains in front of me on the grass. "Thirty-nine," says Sanderson. But looking at Colonel Mackenzie's ball – a fine shot, half-volley, right over the Horse's Arse! – my mind sharpens, concentrates. My next shot connects with a satisfying click, and the ball skims the ground two metres high, and rolls forward past Sanderson's one.

'Still finding your form," says the Colonel politely.

"Not so much that,” Sanderson explains. "It's this being immaterial, you see. With a golf ball that's still part of the real world. Never going to connect properly, nature of things." He addresses his own ball.

The presence of the live human is upping his game as well. His shot connects first time, trickles all the way to the lip of the bunker. "Good shot," I say. "Maybe a bit too far to the right, though."

"Twenty-five for me," Sanderson says. "Your shot I think, Fraser."

The Colonel ranges across the fairway, picks up a cigarette end she's spotted. The three turkey buzzards flap over, their wings creaking, their feathers dull brown in the early sunlight – Colonel Mackenzie, being still alive, doesn't see the turkey buzzards. "That must be most frustrating," she says.

"Bad golf," Sanderson says, "is still golf. We just have to play the ball as it lies. There's time to finish this hole, anyway, before the members start arriving." He chooses his three-iron, and tops his ball into the Horse's Arse. "Twenty-six. Leaving me thirteen in hand to get out of this bunker."

Once on the green, Colonel Mackenzie lifts out the pin – a treat for us two, the metal pole's far too heavy for us to lift and we usually have to hole out with it still standing in the way. Sanderson, thirty-two. Fraser, forty-nine. Colonel Mackenzie: three.

"Members don't seem to be arriving yet," Sanderson says. "Maybe even time for another hole?" In the normal way, after holing out at daybreak, we have to wait for the following night to play the next one.

"They'd normally be here by now. I heard a motor on the driveway, while you were busy in the bunker there. But the car park's still empty."

"Excuse me a moment, Ma'am," Sanderson says politely, before floating up to treetop level to take a look. When he descends to the grass again he's smiling, thin lipped below the pencil moustache. "It's The Secretary," he says. "In that Range Rover of hers. Stream's up across the driveway, you see. Looks like she thought she could get through in that Range Rover. Looks like she aquaplaned on the ford, right into the ditch. Jammed right across, she is."

"Maybe she'll come up to the clubhouse on foot?"

"Not her. Put up the sign, she has. Course Closed. If she can't play, nobody's going to play."

"Nobody except us," I say.

•••

During the walk back under the pine trees, I'm working out how to play this. "Given the mixed nature of the group, I'm thinking of a two-ball. Colonel Mackenzie and myself playing against you, Sanderson." Sanderson playing his own ball: the two of us, the weakest player, myself, and the strongest, Mackenzie, alternating with the other.

We're standing together on the first tee. The sun's up above the oak trees, the dew shining on the grass. In my imagination I'm even smelling the gorse flowers, the fresh grass under our feet. Ahead stretches the first fairway. My first fairway. I made it wide and welcoming – not everyone who comes to the course is a great player, especially straight off the first tee. And there, 200 yards out, the Keltie's Burn cuts across. A really strong player can volley right across the stream. But that strong player gets it just a little bit wrong, and they're in the Keltie's Burn. And that's a two stroke penalty. Sensible players hold back, aim to stop 20 yards short, for an easy five-iron onto the green. A par four, our first hole; but a friendly par four. Unless you get ambitious. If you get ambitious, you end up in the stream.

The Secretary's Range Rover is stuck there for the rest of the day. Which means the course is ours. We're going to play all 18 holes, take as long as we like. All day possibly, given the necessity of our condition, and the way that any attempt to strike a physical ball of the so-called real world is always such a doubtful procedure. But never mind how many strokes it takes. We'll play the hillside Sixth, and the dog-leg Eighth. And of course the Eleventh, the Horse's Arse.

"Colonel Mackenzie. As you're our guest, would you take the honour?"

The Colonel stands at the front of the tee, looking down the fairway. Her shoulders are erect, you can see the remains of her military bearing. "Fraser," she says. "Let me tell you this. Your golf course here: I really love your golf course. The Horse's Arse, yes of course, but all of it. The thought of playing a full round, all the way around – it fills me with intense excitement. It does. Yes." She bends down, places her tee, places her ball with a steady hand. She straightens. She sets up her drive.

The wind's behind us. "Number three driver," I suggest. "With the wooden head?"

"Of course, wooden head. My dear Fraser, what do you take me for?"

She swings back, that slight jerk at the end of the backswing. She's going for the death or glory shot, over the Keltie's Burn.

She goes for it.

I suffer a moment of doubt here. Really, she should have played from the Ladies' Tee, 30 yards further forward. Or, in a mixed-sex two-ball, would that still apply? But my mind clears as her ball rises into the sunlight above the treetops – hangs there for a moment – and drops again into the shadows. My eye loses it then, surely it must be short of the stream. But no, I pick it up again on the bounce, rising gently against the green-black background, rising and dropping, 20 yards beyond the stream and still rolling forward.

A faint sound from behind me then. I turn, and see the Colonel collapsed on the tee, her eyes closed, damp grey hair spread on the ground.

•••

Well, the grass there can be quite slippery until the dew's off it. And a moment later she's up again, and striding down the fairway towards our ball. Behind us, Sanderson's having some trouble teeing off. We're 50 yards down the course before we hear the sharp crunch of club on ball behind us. Having this new opponent has certainly concentrated his mind, because his club has connected, and the ball skitters along the fairway – he's topped it pretty badly, but at least he's hit the thing.

"What's that strange noise?" Colonel Mackenzie asks: standing there, half visible, in the shade of the trees beside me.

"Oh, that's just the wild dogs. They're down at the pond after the ducks, trying to catch them. Which of course they can't do, the ducks being ducks of the real world. Very frustrating for them –"

My voice trails off, rolling to a stop like a golf ball on wet grass. The dogs of the golf course: they're not material beings. The Colonel shouldn't be able to hear the wild dogs. I turn around, look back along the fairway.

There's a dark, humped shape. Still lying on the first tee. Colonel Mackenzie.

"Yes," says Colonel Mackenzie, in the shadows beside me. And there's a smile in her voice. "The Club Secretary's going to be looking for a new supernumerary to tidy up our golf course."

Sanderson's walked up to us now, condoles with the Colonel on her so-recent death. "But what a way to go out! That was quite a drive, 250 yards and right over the Keltie's Burn."

Sanderson's feeling cocky. Now that she's no longer a material being, the Colonel won't be pulling off any more drives like that. And that alters the dynamics. Putting it crudely, Sanderson against myself and the newly deceased Colonel Mackenzie: he's going to wipe us all over the golf course.

Cockiness doesn't really pay: it takes Sanderson six more strokes, plus two penalty for going into the stream, before he's far enough up the course to pass Mackenzie's ball, and it's our turn to play again.

My turn, indeed, under the two-ball rule. The grass is dry now, and my partner's left me a fine lie and a clear line onwards to the green. "Five iron," she suggests quietly. She's right. Five iron.

I address the ball. Despite the sun now shining straight along the fairway, there's a sort of shadow hanging over it. But it's Mackenzie's own ball, I followed it with my eye, and there's no other one lying anywhere on the fairway – striking the wrong ball, that would lose us the hole, but no risk of that here.

I set up my backswing, and take a moment to calm my mind. Failure to at least impose some forward motion on the golf ball will seriously demoralise my partner at this point. But I've a good feeling on this one, this one's going to connect: out there in the material world, the ball's going to make several yards up the fairway, maybe even compel Sanderson to take the follow-up straight away.

I swing. And feel the club connect, the satisfying clunk as my club hits the dubious interface between our immaterial world and the real golf course.

But what's going on? As I look ahead along the fairway, I don't see my ball. Why isn't it rolling along the fairway, 15 or 20 yards away? Have I somehow managed to slice the thing right into the bushes?

And then, out of the sky, a single golf ball drops into my vision. A ball that falls away down the fairway, drops to the edge of the green, rolls forward, and comes to rest. Comes to rest just two club lengths from the pin.

"My god, Fraser! What did you just do there?" Sanderson is seeing himself not just losing the hole, but losing it by over 20 strokes. Sanderson and me, we go back just short of 100 years now. In all that time he's only lost the hole twice. And one of those was when a duck took off with his ball, back before they changed the rule on Ball Comes to Rest on Animal or Bird. But there's this thing about Sanderson: a good shot is a good shot, even if he didn't make it himself.

And now I'm remembering the odd look of darkness about that ball. The sound of it and more than the sound, the feeling as I took the stroke. Almost, but not quite, the same as it used to be, all that time ago, when I was a living golfer striking a golf ball of the material world.

"Colonel, do you realise what you've done? That drive of yours, straight off the tee. You didn't just drive the ball 250 yards up the fairway and across the Keltie's Burn here. You drove that golf ball right out of the material world."

It's gone quiet, here in the afterlife of the first fairway of this course I built over 120 years ago. The Keltie's Burn, having done its job on the Secretary's Range Rover, is murmuring its soft watery words under the little wooden bridge. The turkey buzzards have settled to roost. Hector Sanderson is looking away, polishing the head of his driver. And I know what he's thinking.

Colonel Mackenzie, playing with her non-material ball, is going to run away with it. Nothing lies ahead, now, but being beaten, on every hole, by ten or a dozen strokes.

But the Colonel's been playing golf almost as long as Hector has; and she seems to know how he feels. "We should play it one-ball," she says.

Sanderson looks up. "You mean: non-competitive golf? The three of us playing in turn, to get this single ball around the course?"

"One could look at it as playing against Mr Bogey. Against Fraser here, if you like. He's the man who set par around this course."

"My dear Hector," I say: "It would seem that you have the pleasure of the next shot. Two strokes on the card. Hole this one out for the birdie."

"Ready golf!" says Mackenzie. An inappropriate comment, but excusable in the circumstances. We cross the little wooden bridge – red paint flaking a bit, I'd have a word with The Secretary if I were still alive and paying a subscription. The turkey buzzards are lined up along their branch of the dead pine tree; away on the seventh fairway the feral dogs are baying. Colonel Mackenzie brushes away a worm cast, and Sanderson lines up his putt.

It's a long one, but something tells me he's going to hole it out.

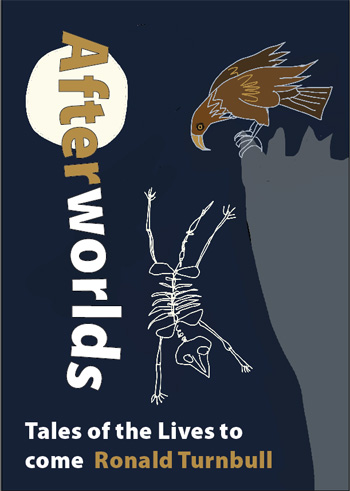

'Golf Balls of the Material World' is one of 13 stories in Afterworlds: tales of the lives to come, which I'll be putting out as an ebook during 2025.

© Ronald Turnbull 2024

Cover illustration © Rosey Priestman