Walkers on the Way

The West Highland Way was thought out in the 1960s, and opened in 1980 by William Mungo Murray, 8th Earl of Mansfield and Mansfield (then Minister of State in the Scottish Office). But in a sense it has always been here. Between the Lowlands and Lochaber have travelled clansmen and cattle thieves; redcoats, drovers, saints and Sir Walter Scott.

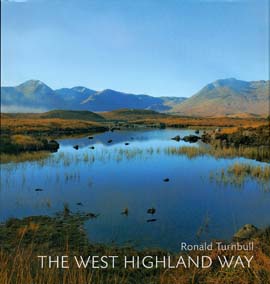

It's a journey of glens and low passes, under the crags and high grassy sides of seven of Scotland's hill ranges: from the Arrochar Alps of Loch Lomond to the Black Mount of Argyll, the Mamores and big Ben Nevis. Geologically, it's an outing from the Old Red Sandstone hills of the so-called Lowland Valley, through the immeasurably older grey schists of the Southern Highlands, to the great volcanic cauldron of Glen Coe. And as it unfolds under the foot, it's 95 miles of heather and oakwood, of lochside and riverside and old railway line -- but also the whole life and history of Celtic Scotland.

First inhabitants of the land were the mythic Fingalians, led by Fingal himself. Larger than life Ð in the literal as well as the metaphorical sense Ð they hunted the deer with their equally oversized dogs, and used their spear-shafts to pole-vault across the narrow sea lochs of Argyll. They fought great battles among themselves and against invading human beings out of Norway, and had commerce with the fairy folk. Along the West Highland Way no trace of them remains; but Deirdre (of the Sorrows) and her first lover Naisi spent happy months with deer hounds around Buachaille Etive Mor, before her tragic fate started to fall upon her. And a short diversion into Glen Coe will show the cave, high among the crags of Bidean nam Bian, named in legend as the home of the Fingalian bard Ossian.

The starting point for the merely human history of the Highlands is almost as mythical: the pre-feudal clan society remembered in songs and stories, but only recorded in writing as it came to its end, and then mostly by the pens of its enemies.

In each glen, the clan lived under its chieftain as an extended family. The traditional 'black house' was of unmortared stone, thatched with heather, and with an earth floor. Peat smoke filled the house before trickling out of the doorways and unglazed windows. Thus it was an effective deterrent against midges, while scenting the rooms with a wild bog smell, with golden sunbeams cutting through the brown gloom. Their music was the clan piper, and entertainment was the bard at the fireside, with tales of past warfare, the fairies, and the Fingalians.

Oats and kale were raised in the more fertile corners of the valley floor, and there would be fish out of the lochs and rivers. But the mainstay of the clan was its cattle: the small, nimble black beasts of the glens. Every summer, to protect the crops, the cattle would be moved up into the high corries. There the young people would live alongside them in temporary huts or shielings, making cheese, and also presumably music and love, in the shelter of the great crags.

And if cattle were the mainstay of clan life, the thieving of cattle was their main economic activity. Bill Murray in his biography of Rob Roy describes cattle-reiving as 'a robust form of social security', redressing the balance when famine struck one part of the Highlands while another was in relative plenty.

In the course of cattle raids in particular, the clansmen made journeys from one side of Scotland to the other, in all weathers, with no shelter apart from their close-woven woollen plaids. For the returning raiders of Lochaber or Argyll, Rannoch Moor was a place of safety; no pursuit would follow into the secret pathways amongst its bogs and lochans. In 1686, the Glencoe MacDonalds came home from the battle of Killiecrankie by way of Glen Lyon. There they raided and stole from the Campbells to the value of £8000 Scots, before heading north by Loch Tulla and the Moor of Rannoch.

Six years later, that same Campbell of Glenlyon came north to Glen Coe with orders for the massacre in his saddlebag. The MacDonalds of Glen Coe, the most successful reivers of them all, had been raiding their neighbours right into the century of the coffee-house and the powdered wig; and were to pay a deadly price for their outmoded traditional lifestyle.

There are, traditionally, three plagues of Argyll: the bracken, the midges Ð and the Campbells. Clan Campbell, under its chieftain the Duke of Argyll, caught on to the possibilities in the new feudal system and started a 200 year campaign to take over the whole of the southern Highlands. Among their principle victims were MacDonalds of Glencoe and the Hebrides, and the Macgregors of Lomondside and the Trossachs.

Their takeover techniques were not genteel. In 1499 they kidnapped the four-year old heiress of Cawdor, kept her captive until she reached 15, then forcibly married her to a Campbell younger son. An heiress widow was seized and raped, while bagpipes played to cover her screams.

Later technique was more sophisticated, but just as effective. A feud between Clan Gregor and the Colquhouns of Loch Lomondside started with the unauthorised slaughter of a black-tailed sheep. Campbell of Argyll offered support to the Macgregors, encouraging them to kill two or three hundred of the Colquhouns. At this point the Campbell rode over to Edinburgh and offered to sort out the problem. Thus in 1603 the whole of Clan Gregor was declared outlaw and the use even of its surname was banned. This stayed on the statute book for almost 200 years, being reactivated as convenient to the Campbells.

|