|

| |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

|

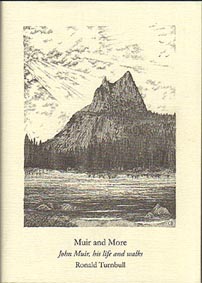

Muir and More

John Muir, his life and walks Millrace Books, 2008Hardback 180x130mm, £14.95 (direct mail £13.50)

184 pages 11 B&W line drawings by Colin Brash, old photos, sketch maps

ISBN 978 1 902173 27 6

Cover: Cathedral Peak and its lake, by Colin Brash

John Muir -- a life, but also a hike. Muir is 200 miles of high-level granite and pine, but also the inventor of a clockwork self-awakening bed and the American national park system. Muir is East Lothian's Man of the Millennium -- this despite the fact that he left Scotland for ever at the age of eleven -- and one of the best long paths in the world.

Award-winning writer Ronald Turnbull is the first and probably the only person to haved walked both California's John Muir Trail and East Lothian's very different John Muir Way in a single season. Between the cold grey waters of the Forth and the sunlit rock-slabs of California he consideres the cult of vegetable worship, the paradoxes inherent in the preservation of wilderness, and the fascination of 200 miles of granite. He tastes both the huckleberry and the deep-fried haggis, and contemplates the sexiness of pebbles and of Henry David Thoreau's chin-beard. But most of all, he meets John Muir himself -- inspired visionary and tiresome tree-hugger; the exiled Scot who invented the American outdoors.

For John Muir is more than a source of sweetly-scented outdoor quotes. In this world of wind farms, nuclear power stations and big people-crusher cars, Muir matters.

reviews

Through the letter box at Outdoors Station Studios -- just in time for Christmas -- comes this new offering from Millrace Books.

The central figure is John Muir, the man from Dunbar on the East Coast of Scotland, who journeyed across and made his name exploring the wilderness of North America. Muir is a man who inspired much of what can now be seen as modern backpacking. His work, actions and campaigning led to the creation of the first national park, the forerunner of those throughout the world including our own here in Britain. Today, here in the UK, Muir is remembered through the work of the John Muir Trust that is preserving the last of our last great areas of wild land, for example, much of the the Knoydart peninsular of North West Scotland.

Ronald Turnbull is, of course, one of the UK's most prolific outdoor writers. He is also one of our funniest and most eccentric. Is eccentric the right word for Ronald? Maybe. But he is also very funny, a touch cheeky even.

So, put these two characters together and we should have a great book. And so we do.

Central to Muir and More is Ronald's walk along the North American John Muir Trail, that runs from Yosemite through the Sierra Nevada South East to Lone Pine. I spent a day with Ronald, up at Cicerone Books not long after he had completed his walk. You can hear Ronald talking to Bob Cartwight about the John Muir Trail here. [okay, I'll fix this link back in - RT]

This is no guide book though. Muir and More uses the story of journey that Ronald made with his son Tom, to tell us much about John Muir, his exploration and his life's work. Muir was a fascinating character, one of those rare people who literally changed the way in which many of us see the world and choose to live our lives. There's just enough here to get you hooked on Muir and to encourage you to explore his own writings and look up some of the more conventional biographical material. Personally, I find much of Muir's writing a bit too flowery but when you read his accounts of his wandering you're left in no doubt that you are experiencing something that was -- in its own time -- as important as, say, the first summit of Everest.

But there's more still to this book that the trail and John Muir. Ronald uses the walk to spin off in all kinds of tangental directions. There's a lot on geology. There's quite a lot of stuff on bears (bears being one of the hazards of the JMT). How about a section all about the Huckeberry (or the bilberry or the blueberry)? Then there's Ronald's thoughts on mountains in general, on the Lakes, on his beloved Highlands and on some of the other areas he's visited. (Read this and you'll probably strike the Tatras off your list of mountain regions to visit before you die). Oh, and he's not a fan of the Himalayas, or at least of organised treks through it.

These tangental wanderings are something of a characteristic of Millrace Books (see my previous review of Tips of the North by Graham Wilson). I can almost hear the first conversation between publisher and write-to-be. "And go off all over the place. We love tangental thought. The more you can write about anything other than the subject -- the better it is!"

We should all be grateful for this approach for it delivers us very unusual and entertaining books. So, Muir and More is at once informative, entertaining and very funny. But did I mention that Ronald can be, well, just a little cheeky? Here there is quite a lot of thinking about naked women! There's the huge Scots Woman and the dinner, whose nether regions seem to spread over three chairs; Ronald can't resist thinking of what she would look like naked. There are young, female, hikers stripping off and swimming in lakes (who may or may not have been snapped by the naughty chappie himself). And there's Ronalds great observation that Ansell Adams missed a great trick when he took his stunning black and white studies of these same mountains: the shots would have looked a lot better with a naked women in the corner!

This is a great book that will entertain many. I should add that it also features the other John Muir Way, a somewhat less inspiring walk along the southern shores of the Firth of Forth (around Dunbar of course). Indeed, Ronald fancies that he is probably the only person to have hiked both John Muir Trails in one hiking season.

This is a great short read, the narrative being only 170 odd pages long. I was pleased to have it to read in one setting while I was laid out suffering from an early winter virus.

Millrace are one of our smaller publishers and the first print run of the book is only 800 copies. It comes as a lovely, pocket sized hard-back, perfectly shaped to slip into the rucksack to read in the tent or on public transport as you head out, or set back, from the hills. Snap one up quickly! Andy Howell, the Outdoors Station, Dec 2008