How Blencathra Became

It's odd to think, as you stand on Blencathra's 868m summit, that it started life as sludge 6000m under the ocean.

That ocean was called Iapetus. It existed eight geological ages ago, somewhere in the southern hemisphere. What would eventually be called England was at its southern edge. Standing on that coastline, 450 million years ago, you'd be on bare brown ground and probably in a dust storm -- as land plants have yet to invent themselves. Off shore, you might see a chain of volcanic islands, bare and black, possibly with grey ash-clouds, or with white clouds of steam as lava hit the ocean below. (Or of course, you might not: there are those dust storms, and there is also the fog of 450 million years of everything happening since, so that the volcanic islands are no more than a pretty good guess.)

Beyond the black steaming islands was a deep ocean trench, as there is today off the volcanic shores of Japan and of South America. And if you watched really, really closely over several millennia, you noticed the land at the other side getting very slowly closer. For the Iapetus Ocean was shrinking, its bed being drawn down underneath 'England' in what geologists call a subduction zone. Eventually, in the geological period called the Devonian, the ocean closed up completely, as what would eventually be Scotland arrived from the other side. This collision of the continents squashed the sludge, and very gradually raised it into a mountain range called the Caledonian. This range was as high and jagged as similarly-formed ranges of today, the Alps (Italy crashing into Europe) or even the Himalayas (India's collision with Asia).

The lumpy landscape of Helvellyn and the Scafells is the crushed remains of that chain of volcanic islands just off the southern continent's northern shore. Their rock is called 'Borrowdale Volcanic'. Beyond the islands lay the sludgy-bottomed ocean trench. Squeezed-up sludge forms slate; so the rocks of the northern fells are slaty, and were formerly called the Skiddaw Slates. As some of them are actually greywackes or grey sandstone, they are now officially referred to as the Skiddaw System. But almost all of them are somewhat slaty, and I'll use the old name in this book.

Formed 500 million years ago, these are among the oldest surviving rocks in England. The Earth itself is nine times as old as the Skiddaw Slates, and even the Universe is only 30 times as old.

Cumbria, however, is not Caledonia. Ages of erosion through half the geological history of the planet have totally erased those Caledonian mountains. They ended up so flat they were actually underwater, with kilometres of limestone and sandstone over the top. But then the sudden arrival of Africa rumpled up our corner of Europe, and raised these tough old rocks again from the deep underground. It's only taken a couple of hundred million years for the come-lately limestone and sandstone to erode off again. This leaves the now twice-crumpled grey slates standing proud; along with the purple-grey or greeny-grey volcanic rocks to their south.

In the last eyeblink of geological time, the glaciers of the current Ice Age have given the slates and the Borrowdale Volcanics the shapes they happen to have, at the unimportant moment we call now.

Slate splits into thin sheets: that's what makes it slate. It splits like this because, as the rocks get squashed, little flat crystals of mica realign at right angles to the compression. The sludge destined to become Skiddaw made a sort of slate that's not useful for covering your roof with. Instead it falls apart into little saucer-shaped pebbles, as found on the pathways of Blencathra. The smooth, shiny mica, lined up along the splitting-apart surfaces, means that these slaty rocks are slippery. If you're used to the rough volcanic rocks of central Lakeland, you'll find Sharp Edge slightly treacherous, and especially so in the wet. Cairns made of the Skiddaw Slates tend to slide apart. The one at Blencathra summit comes and goes: during the mid-1990s it didn't exist at all. Even when it's there, it's a sad stonepile that slumps into the plateau like a mud pie left out in the rain.

The Central Fells -- Helvellyn, Scafell, Great Gable -- are made of tough volcanic rocks: and their shapes are cragged and chunky. The northern fells, made of Skiddaw Slates, have smooth, steep sides, formed of bare scree or of scree covered in heather. The compensation is the fine ridgelines. Blencathra has Sharp Edge and Halls Fell, as well as Gategill and Doddick Fells. The Grasmoor group also has fine (if somewhat slippery) ridges; and even Skiddaw, the somewhat dull neighbour of Blencathra, has Long Side.

The underlying rocks determine the soil, and the plant life that grows out of it, and even the sheep that eat the plants. Particular incidents within the great earth movements give character to Carrock with its odd volcanics, or play out the sequence of altered metamorphic rocks on the way up Glenderaterra. Mere details within those details are the mineral intrusions that, along with the sheep, give these hills their social history. So the logical unfolding of this account means that next will come a sequence of sub-chapters on the detailed geology; then the flowers and wildlife growing out of it; then the human history of mining, farming and, finally, of fellwalking – itself determined by the underlying geology.

But I'm a fellwalker, and to that logical unfolding I say: I can't wait that long.

So this book is now going straight up Blencathra, starting by its finest and most exciting route, Scales Tarn and the scramble of Sharp Edge. It will then work around clockwise, by the five front ridges, not to mention their intervening ravines. After that it will wander up Glenderaterra, and cock a snook at the big brother Skiddaw itself. The biology and the geology, the lead and tungsten and zinc, the wild flowers and the even wilder Herdwick sheep; they are all out there on the slopes of Blencathra, and with any luck we'll come across them all by the time we reach the three delightful outliers at Blencathra's eastern end: Bowscale and Bannerdale, and the smaller Souther Fell.

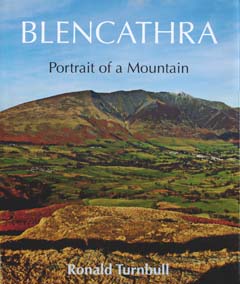

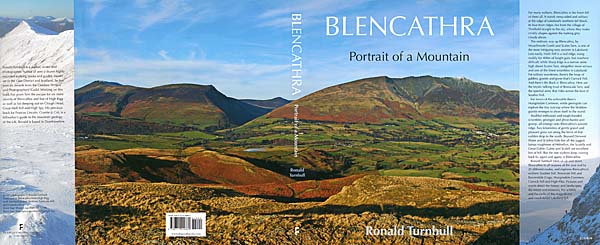

Youthful enthusiast and rough-handed scrambler, geologist and ghost-hunter and grump, all emerge alike onto Blencathra's two kilometres of summit ridge. And there we stroll on gentle gravel and pleasant grass, along the brink of that sudden drop to the south. Beyond Derwent Water and St John's Vale, there is laid out in panorama all the jagged, lumpy roughness of Helvellyn, the Scafells, Great Gable. Gable and Scafell are excellent bits of hill. But the one walkers keep coming back to, again and again, is Blencathra.

|