|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

A Long Walk – and a Broad Stand

You've heard of ridge walking. Ronald Turnbull goes Cole-ridge walking: back into the past and off the edge of ScafellLakeland Walker magazine, September 2002

5th August 2002

Dear Lakeland Walkers

it’s a grey sort of day up here on Scafell. I’m standing at a natural writing desk on the little rockpile called Symonds Knott. From here I look right down onto Wasdale Head. Between me and the valley floor, grey cloud is swirling around like soapy water that won’t go down the drain. The tops of Scafell are as grey as a humid hazy day can make them – grey rock, grey-green woolly moss, and the half-clouded top of Gable looking grey a little way away. Even here at 3000ft the air just flops around the summit, like a sweaty exhausted walker. A bewildered butterfly just flew past, and small midges are landing on my fingers as I write.

My reason for writing to you today, from here, is the date at the top of the letter. 200 years ago, on 5th August 1802, the poet Coleridge made the first recorded ascent of Scafell – and sat down on the summit to write the first ever Scafell letter.

He came here from Keswick over several days, by a slow and roundabout route which I’ve just been following, more or less. Over Newlands for dinner at the Fish Inn – the barman who served me wasn’t strikingly good-looking, but Coleridge was served his 18th-century equivalent of lasagna and chips by the Maid of Buttermere herself. Out to St Bees – not famous then as the start of the Coast to Coast Walk. He went and looked at the cliffs and wasn’t that impressed. He went and looked at the Abbey but didn’t take a photo as they hadn’t invented the camera yet. He stopped for a night at Wasdale Head, and came up the coffin path from Brackenclose and the long grassy slope above. He reached the top at about 2 o’ clock, looked at the views down into Hollow Stones and all the way back to Keswick, and found a sheltered corner to write them all down.

And then he folded his paper, put away his pen, and set off for Mickledore the crag-dangly way. The rest of the letter would have to wait.

Bears and St Bees

And then he folded his paper, put away his pen, and set off for Mickledore the crag-dangly way. The rest of the letter would have to wait.

Bears and St Bees

| top |

The routes Coleridge walked in 1802 are now mostly roads, and to walk on roads where the poet walked on rough tracks and paths wouldn’t be authentic. More importantly, it wouldn’t be fun. I had aimed to recreate the spirit, rather than the exact route, of 1802. First I paid a visit to Greta Hall, which I found surrounded by the Greta Hamlet housing estate. I headed out of Keswick over Barrow, for no poetic reason but because I’d never been on Barrow. Barrow is a nice small hill, swimming in summer haze, but on its top a reluctant family was complaining about the fells. “Why do we want to go on to that one over there? We’re already higher up than it is right here where we are.” This raises the more important question of why we came up Barrow in the first place, and on such a hot afternoon. But since the answer would only be because Daddy pretended fellwalking was going to be fun, I postponed the philosophy and pressed on over little Ard Crags to the Newlands Pass.

It hadn’t been raining much on Coleridge; and so he noted Moss Force as too dry to be worth a detour and passed on over the Newlands Pass. Three weeks later, he returned to see it after some proper Lakeland summer weather. His description of the fall in full spate takes up two pages of his notebook, and the accuracy and passion of it are an embarrassment and a rebuke to any Lakeland writer of today, including me. Was Coleridge not just the first fellwalker, but the last fell writer?

The mad water rushes through its sinuous bed, or rather prison, of rock, as if it turned the corners not from mechanic force, but with foreknowledge, like a fierce and skilful driver. Great masses of water, one after another, that in twilight one might have feelingly compared them to a vast crowd of huge white bears, rushing one over the other against the wind – their long white hair shattering abroad in the wind.

Sadly, it wasn’t raining at all as I came through Newlands, and the hairy white bears were back in the sky waiting for the next storm. The scramble beside the waterfall, where he got into difficulties, is now brushed clean by many feet. In dry weather it was not problematic, and gave me a good view of the upper fall. The “one great black outjutment” that pierced the fall in 1802 outjuts there still.

The mad water rushes through its sinuous bed, or rather prison, of rock, as if it turned the corners not from mechanic force, but with foreknowledge, like a fierce and skilful driver. Great masses of water, one after another, that in twilight one might have feelingly compared them to a vast crowd of huge white bears, rushing one over the other against the wind – their long white hair shattering abroad in the wind.

Sadly, it wasn’t raining at all as I came through Newlands, and the hairy white bears were back in the sky waiting for the next storm. The scramble beside the waterfall, where he got into difficulties, is now brushed clean by many feet. In dry weather it was not problematic, and gave me a good view of the upper fall. The “one great black outjutment” that pierced the fall in 1802 outjuts there still.

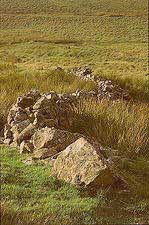

In late afternoon I passed through Buttermere just in time for an early bar meal at the Fish, and then on the true Coleridge route through the Floutern Pass. Today, as in 1802, it’s “every man his own pathmaker” around the head of Mosedale. Coleridge’s principle: “where rushes grow, a man may go” is as useful as ever. The ruined sheepfold induced exactly the mood he felt like being in on that August evening:

... a wild green view all around me, bleating of sheep and noise of waters. I sat there near twenty minutes, the sun setting on the hill behind with a soft watery gleam... Of all things, a ruined sheepfold in a desolate place is the dearest to me, and fills me most with dreams and visions and tender thoughts of those I love best.

The sheepfold stands, still more romantically ruinous, today.

... a wild green view all around me, bleating of sheep and noise of waters. I sat there near twenty minutes, the sun setting on the hill behind with a soft watery gleam... Of all things, a ruined sheepfold in a desolate place is the dearest to me, and fills me most with dreams and visions and tender thoughts of those I love best.

The sheepfold stands, still more romantically ruinous, today.

| top |

Coleridge in his day was a 30-mile man, and his friend Wordsworth as well. Indeed Wordsworth’s sister Dorothy was a 30-mile woman, as the three of them tramped over Exmoor and Yorkshire as well as the Lakes. On Day Two I decided to imitate them with a 30-miler of my own. This took me down Wainwright’s coast-to-coast to St Bees Head. “St Bees Head might be made a song of on the flats of the Dutch coast – ” said Coleridge, “but in England ’twill scarce bear a looking-at.”

Next I discovered that the Cumbria Coastal Way does exist, sort of. Sellafield – from afar the place has a sort of drama, whether its distorted chimneys gleam in early sun from Dent Fell, or lift out of sea haze above St Bees. Close up, though, it’s all high fencing and razor wire. And a notice tells you that if you die of radiation sickness on the way past it’s not their fault.

Next I discovered that the Cumbria Coastal Way does exist, sort of. Sellafield – from afar the place has a sort of drama, whether its distorted chimneys gleam in early sun from Dent Fell, or lift out of sea haze above St Bees. Close up, though, it’s all high fencing and razor wire. And a notice tells you that if you die of radiation sickness on the way past it’s not their fault.

|

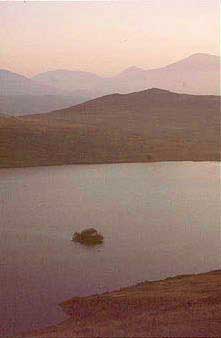

Nightfall saw me dossing down on Buckbarrow. Far below, evening light skittered across the face of Wastwater. Cloud fuzzed like old man’s knuckle-hair among the bent fingers of Middle Fell. How Coleridge would have enjoyed the bivvy bag – when no friendly farmhouse presented itself, he just rolled up in his coat, and pulled on a cotton nightcap for wet-weather protection.

Buckbarrow has cosy corners among the rocks, whose only defect is that if people like me appreciate them, then so do sheep. As I sat up to eat a midnight snack, a spark of light in the grass beside me seemed to be a glow-worm. It wasn’t. It was the lights of the youth hostel, a thousand feet below. And at the head of the valley, in the sunset-edged darkness, Scafell did look very big.

A broader understanding of Broad Stand

A broader understanding of Broad Stand

| top |

Which brings me – and Coleridge too – back to the point where we laid aside our letters. What happened next to Coleridge has been considered by the Fell & Rock Club as England’s first ever recreational rock-climb. He set off in the general direction of Scafell Pike, found that the ground got rather steep and rocky, and carried on by dangling and dropping from ledge to shelf. The problem with this is that if you get into trouble it’s not usually possible to dangle and drop back up again. And so he found himself on the little triangular ledge of what is today called Broad Stand.

And now I had only two more to drop down – but of these two the first was tremendous. It was twice my own height, and the ledge at the bottom was so exceedingly narrow, that if I dropped down upon it I must of necessity have fallen backwards and of course killed myself.

This isn’t what I’d call rock-climbing. This is what, if I’d done it myself, I’d call sheer stupidity. And so does Coleridge.

I was beginning according to my custom to laugh at myself for a madman, when the sight of the crags above me, and the impetuous clouds just over them, posting so luridly and so rapidly northward, overawed me... O God, I exclaimed aloud, how calm, how blessed am I now.

Glancing round to the left, he noticed the deep crack, now called Fat Man’s Agony, that leads down to the Mickledore screes. Since Coleridge’s time, the grass and loose stones have all been kicked away, and the route is reassuringly obvious. And this does make all the difference: “Nice to see someone who knows the way,” said the man coming down behind me. I didn’t spoil his touching faith by letting on that I was a non-climber already rendered thoroughly nervous by several readings of the famous Scafell Letter.

| top |

Broad Stand is one of the Wasdale Rescue Team’s black spots. Their commonest callout is for people coming off Scafell Pike the wrong way and ending up in Eskdale – six so far this year. But their second commonest callout is Broad Stand.

All those Victorian climbers in their nailed boots, who kicked away the moss and grass, have also left the footholds rather smooth. In the wet, they get slippery. The most recent rescue on Broad Stand involved a runner in the annual Lakes Threethousands event. In rain and strong wind, he made his way up the Coleridge pitch using a rope already in place, only to slip from the easier rocks above. He fell 50m down Mickledore Chimney, suffering injuries to his head and legs. Earlier in the year, a walker fell from the rock-pitch to the screes below, injuring his head and breaking his ankle.

With the rocks dry, the route known, and a rope to lower the rucksack, Broad Stand wasn’t too bad. But it is possible, simply by not reading guide-books and magazines, to recreate the 18th-century exploratory experience. The man behind me had just got on Scafell by free-climbing Mickledore Chimney, grade Difficult.

Exaltation or dismalness

Coleridge was a Romantic. For him a poet’s purpose was to experience particularly vivid feelings – whether the exaltation of opium or the dismalness of not being much good as a poet (Dejection: an Ode). He went to Moss Ghyll and Scafell in pursuit of very specific sensations.

Sometimes the sensations were pleasant ones – and the scenery would be categorised as beautiful, or even worse, picturesque. Altogether better were places that induced feelings of awe, and even terror. Such scenery was described as ‘sublime’. Romanticism would lead, in another 20 years, to Frankenstein and Dracula. But in the meantime, Coleridge had to make do with the view (“the frightfullest cove that might ever be seen, huge perpendicular precipices!”) from Symonds Knott.

And clearly he’s on to something here. A day on Broad Stand is more rewarding than a day on Broad Law. And Stephen King wouldn’t sell the way he does if he wrote elegiac verse in the style of the 17th Century.

Ulpha and the ends of fellwalking

All those Victorian climbers in their nailed boots, who kicked away the moss and grass, have also left the footholds rather smooth. In the wet, they get slippery. The most recent rescue on Broad Stand involved a runner in the annual Lakes Threethousands event. In rain and strong wind, he made his way up the Coleridge pitch using a rope already in place, only to slip from the easier rocks above. He fell 50m down Mickledore Chimney, suffering injuries to his head and legs. Earlier in the year, a walker fell from the rock-pitch to the screes below, injuring his head and breaking his ankle.

With the rocks dry, the route known, and a rope to lower the rucksack, Broad Stand wasn’t too bad. But it is possible, simply by not reading guide-books and magazines, to recreate the 18th-century exploratory experience. The man behind me had just got on Scafell by free-climbing Mickledore Chimney, grade Difficult.

Exaltation or dismalness

Coleridge was a Romantic. For him a poet’s purpose was to experience particularly vivid feelings – whether the exaltation of opium or the dismalness of not being much good as a poet (Dejection: an Ode). He went to Moss Ghyll and Scafell in pursuit of very specific sensations.

Sometimes the sensations were pleasant ones – and the scenery would be categorised as beautiful, or even worse, picturesque. Altogether better were places that induced feelings of awe, and even terror. Such scenery was described as ‘sublime’. Romanticism would lead, in another 20 years, to Frankenstein and Dracula. But in the meantime, Coleridge had to make do with the view (“the frightfullest cove that might ever be seen, huge perpendicular precipices!”) from Symonds Knott.

And clearly he’s on to something here. A day on Broad Stand is more rewarding than a day on Broad Law. And Stephen King wouldn’t sell the way he does if he wrote elegiac verse in the style of the 17th Century.

Ulpha and the ends of fellwalking

| top |

After leaving Dunnerdale, Coleridge got lost in the Dunnerdale Fells, and found himself back in Dunnerdale in time for lunch. Coleridge’s map was a sketch, copied (slightly wrong) from another sketch in West’s guidebook.

My map is Harvey’s. And some of my dreams are map dreams: like the way the Dunnerdale Fells carry on into Caw, and Caw leads eventually to Dow Crag, and that’s a day that can only end by coming down off Wetherlam by way of Steel Edge.

“Philosopher in a Mist” – that’s how Coleridge described himself in a letter he wrote from the roof-leads at Greta House. And that’s how it was when I woke next morning on Loughrigg; except that I wasn’t being very philosophical about it. I stuffed the bivvybag in the rucksack and prepared to get wet.

Come into Grasmere Town End at 7am by the old road over White Moss, and ignore the cars as well as the tarmac they’re parked on. Town End does look like pictures of 200 years ago; when the convivial Dove & Olive Branch Inn was newly converted into the austere little household of those peculiar poet people. By August of 1802, the jasmine and roses planted by Dorothy Wordsworth were starting to cover the starkly whitewashed walls that Romantic poets found so objectionable. However, the Wordsworth people were away – in 1802, they were in France settling affairs with William’s French mistress and love-child so he could marry Mary Hutchinson – 2002’s Wordsworth people simply hadn’t arrived for work yet. I went up between the museum and the cottage, and looked behind an oak branch to find the STC initials carved into a broken piece of stone.

My map is Harvey’s. And some of my dreams are map dreams: like the way the Dunnerdale Fells carry on into Caw, and Caw leads eventually to Dow Crag, and that’s a day that can only end by coming down off Wetherlam by way of Steel Edge.

“Philosopher in a Mist” – that’s how Coleridge described himself in a letter he wrote from the roof-leads at Greta House. And that’s how it was when I woke next morning on Loughrigg; except that I wasn’t being very philosophical about it. I stuffed the bivvybag in the rucksack and prepared to get wet.

Come into Grasmere Town End at 7am by the old road over White Moss, and ignore the cars as well as the tarmac they’re parked on. Town End does look like pictures of 200 years ago; when the convivial Dove & Olive Branch Inn was newly converted into the austere little household of those peculiar poet people. By August of 1802, the jasmine and roses planted by Dorothy Wordsworth were starting to cover the starkly whitewashed walls that Romantic poets found so objectionable. However, the Wordsworth people were away – in 1802, they were in France settling affairs with William’s French mistress and love-child so he could marry Mary Hutchinson – 2002’s Wordsworth people simply hadn’t arrived for work yet. I went up between the museum and the cottage, and looked behind an oak branch to find the STC initials carved into a broken piece of stone.

| top |

This is the Rock of Names. Here Coleridge must have badly blunted his penknife as he cut his own initials a few months before the Scafell walk. He also cut SH for Sara (known as Asra) Hutchinson, the woman he wrote his Scafell letter to. (Sara/Asra, the one he fell in love with, became Wordsworth’s sister-in-law. Confusingly, Coleridge’s wife, also called Sara, was the sister-in-law of the poet Robert Southey.)

The Rock of Names formerly stood above Thirlmere, where Wordsworths, Hutchinsons and Coleridge often met between Greta Hall and Grasmere. The stone was blown up to make the reservoir road, rescued in pieces by Canon Rawnsley. Handy of the Canon to bring the stone down to Grasmere, as it gave me an excuse for not walking up Dunmail Raise – through by Thirlmere is no longer a walkers’ way to Keswick. I decided to take the ridge route over Ullscarf; I’d never been on Bleaberry.

I’ve said that the Scafell walk of Coleridge was the first ever taken for recognisable fellwalking reasons. That still leaves open the question of what those reasons are. Ullscarf to High Seat, in low cloud and ever-heavier rainfall, is about as unexciting as it gets. It could almost be part of the Pennines or the Southern Uplands. A sad-looking fence plods its way across, moulting iron wire into the bog. I could take the path beside the fence, wading through the soggy bits as I came to them. Or I could divert around the swamp, when I very soon found myself diverting around the swamp on the diversion, and re-diverting, and then wading through it anyway. From time to time – when I fell over and get my map all mossy – it was necessary to pause for a moment to express my feelings.

For rather artificial reasons, I was pretending I needed to be on Bleaberry. Only 30 Wainwright tops to do, and some of the 30 are actually quite nice hills. Walla Crag isn’t one of them, as it’s not a hill – just a perch on the edge of the reedbed. But its niceness is undeniable. Derwentwater stretched grey below ragged cloud edges. Above Derwentwater the path dodged among trees and rocks just below the craggy rim. On the path a couple of children, dressed for the conditions in raincoat, shorts and pink trainers, were having a fine time on Walla Crag without anyone having to tell them to. And here’s Coleridge, this time on the slopes of Robinson:

I’ve said that the Scafell walk of Coleridge was the first ever taken for recognisable fellwalking reasons. That still leaves open the question of what those reasons are. Ullscarf to High Seat, in low cloud and ever-heavier rainfall, is about as unexciting as it gets. It could almost be part of the Pennines or the Southern Uplands. A sad-looking fence plods its way across, moulting iron wire into the bog. I could take the path beside the fence, wading through the soggy bits as I came to them. Or I could divert around the swamp, when I very soon found myself diverting around the swamp on the diversion, and re-diverting, and then wading through it anyway. From time to time – when I fell over and get my map all mossy – it was necessary to pause for a moment to express my feelings.

For rather artificial reasons, I was pretending I needed to be on Bleaberry. Only 30 Wainwright tops to do, and some of the 30 are actually quite nice hills. Walla Crag isn’t one of them, as it’s not a hill – just a perch on the edge of the reedbed. But its niceness is undeniable. Derwentwater stretched grey below ragged cloud edges. Above Derwentwater the path dodged among trees and rocks just below the craggy rim. On the path a couple of children, dressed for the conditions in raincoat, shorts and pink trainers, were having a fine time on Walla Crag without anyone having to tell them to. And here’s Coleridge, this time on the slopes of Robinson:

| top |

I had a glorious walk – the rain sailing along those black crags and green slopes, white as the woolly down on the under side of a willow leaf, and soft as floss silk. Silver fillets of water down every mountain from top to bottom that were as fine as bridegrooms.

You don’t need a reason, for fellwalking Walla Crag in the wet.

You don’t need a reason, for fellwalking Walla Crag in the wet.

KIT LIST | |

|

STC net knapsack spare clothes (shirt, cravat, two pairs stockings) green oilskin paper and pens book of verse (Voss, in German) nightcap tea and sugar walking pole (kitchen besom with the twigs off) expenses: 13/6d, of which 4/- given to ‘bairns and footsore wayfarers’ |

RT 35 ltr rucksack spare clothes (fleece, tracksters, one pair socks) green breathable waterproof coat paper and biros book of verse (Coleridge) bivvy bag, sleeping bag muesli bars, Mars bars, sandwiches, biscuits expenses: £64.09, mostly on bar meals |

Note: you can read the full text of Coleridge’s nine-day walk, including the Scafell Letter, on Lancaster University's website. The full text of Coleridge's description of Moss Force is on this site. For more about Coleridge get the first volume of the biography by Richard Holmes, called ‘Coleridge: Early Visions’: scholarly but readable.

And Dorothy Wordsworth's description of the first recorded ascent of Scafell Pike 16 years later is here.

|

| top |